Harvard now hosts more students from China than India: A tale of two countries and two choices

For much of the last two decades, the story of international students in the United States came with a familiar refrain: China set the rhythm, the rest followed. But the refrain has changed. Open Doors 2025—the annual snapshot of international enrolments published by the Institute of International Education—puts hard numbers to that shift. The US hosted 1,177,766 international students in 2024–25—a record-ish kind of number that tells you America still sells the world an expensive dream. And the biggest buyer right now is India. 363,019 Indian students were studying in the US that year, making India the top source country. China was second with 265,919.That switch matters because it isn’t just a league-table vanity metric. It reflects how two rising powers are using American higher education differently. India’s wave is propelled by a young, ambitious middle class and a very practical bargain: a US degree that can still translate into work experience, global credibility, and a shot at staying on. China’s flow—once the metronome of international admissions—has become more selective, shaped by stronger options at home and a chillier political climate abroad. The point isn’t that one country has “won” and the other has “lost.” It’s that the centre of gravity has shifted.Now, here’s where the story becomes interesting. National totals tell you who is buying America’s education at scale. But they don’t tell you where the power sits inside the system—which campuses attract which countries, in which schools, and for what kinds of degrees. When you zoom into the highest-altitude institutions, the India–China order can flip. And one university, in particular, makes that contrast unusually stark. When you zoom into the highest-altitude institutions, the India–China order can flip. And few places illustrate that reversal more sharply than Harvard—not as a symbol, but as a dataset with a very different story to tell.

The India–China story Harvard numbers say

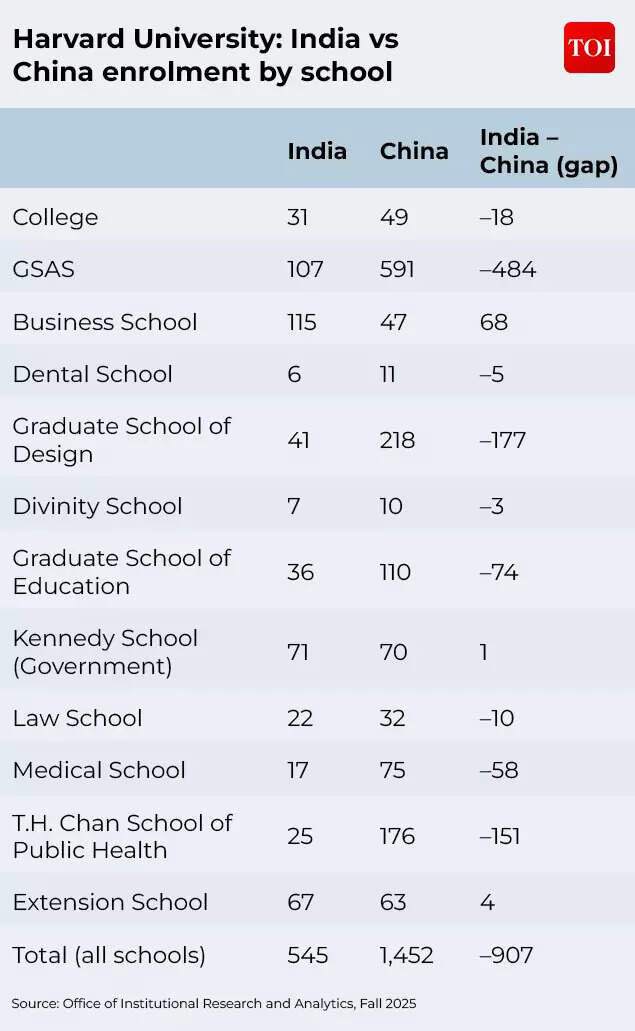

Harvard’s official figures don’t just add nuance to America’s India–China narrative, they complicate it. In Fall 2025, Harvard enrolled 1,452 students from China and 545 from India, according to the university’s Office of Institutional Research and Analytics (OIRA). This is also happening inside a campus that is, by any measure, deeply international. OIRA’s Fall 2025 dataset lists 6,749 U.S. nonresident students out of 24,317 total enrolment — about 28%. So the question isn’t whether Harvard is “global.” It plainly is. The question is which version of globalisation is winning inside the most selective institutions. National aggregates tell you who shows up across America’s thousands of campuses; elite data tell you who penetrates the narrowest gates. India may now dominate the US system in sheer numbers, but Harvard’s distribution hints at something else: where the pipeline is thickest when the competition is fiercest, and where academic depth — especially in research-heavy programmes — still tilts. It’s a reminder that higher education has its own geopolitics. The big headline is about volume. The more consequential story is about placement.

India vs. China at Harvard: A tale of two academic strategies

Totals tell you who shows up. Distribution tells you who settles where. Spread across Harvard’s schools, the India–China numbers stop looking like a numerical imbalance and begin to read like two distinct philosophies of how global talent engages with elite institutions.

In the table, the first thing that stands out is not the overall deficit for India, but where that deficit concentrates. The single most consequential line is Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS), where India trails China by 484 students. This is not incidental. GSAS is Harvard’s intellectual engine room: Home to PhDs, research master’s programmes, and the long apprenticeship that feeds academia, science, and policy research worldwide. Dominance here signals not just presence, but deep institutional embedding. China’s advantage suggests a pipeline that prioritises research continuity—students who stay longer, publish more, and are more likely to circle back as postdoctoral researchers or collaborators.That pattern repeats across other research-heavy domains as well. The Graduate School of Design, T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Medical School all show large China surpluses. These are fields that shape global frameworks: How cities are planned, how public health crises are governed, how biomedical knowledge is produced. China’s footprint in these schools reflects a long-term bet on expertise accumulation rather than quick credentialing. It is slower capital, but it compounds.India’s strength emerges in a different register—Harvard Business School— where India is ahead by 68 students. This fits a wider pattern. India tends to show up most strongly in programmes that turn into jobs quickly—degrees that feed straight into leadership tracks, start-ups, or global corporate moves. The near tie at the Kennedy School underlines that point: Indians are present in force where policy is taught as something you do, not just something you study—implementation, negotiation, governance. But the numbers are not yet large enough to shape the research conversation from the centre. And India’s small edge in the Extension School suggests something else again: a preference for routes that offer flexibility and reach, even if they sit slightly outside Harvard’s core power hubs.Taken together, the table tells a larger story. China’s presence at Harvard is vertically integrated: From undergraduate study through doctoral research and into specialised professional domains that influence global systems. India’s presence is horizontally expansive: Strong in business and policy-adjacent spaces, lighter where time horizons stretch and academic reproduction takes over.

At Harvard, India and China choose differently

It would be tempting to read these numbers as a scoreboard. That would miss the point. What Harvard’s data captures is not a deficit of talent or a surplus of ambition, but a split in strategy: where they place talent, and why. One model directs its most competitive students into long-horizon institutions—doctoral programmes, research cultures, and disciplines where influence is cumulative and authority is earned slowly. The other prioritises velocity: credentials that convert quickly into careers, global exposure that scales fast, returns that arrive early.Neither choice is accidental. Both reflect domestic structures, labour markets, and political economies. But they produce very different forms of presence at the top of the academic pyramid. Harvard does not adjudicate between them; it merely reveals the outcome. In elite spaces, where time, patience, and institutional embedding matter, depth still exerts a quiet gravitational pull. Numbers open the door. Staying power decides who shapes the room.